The Starmer Sanction: A chronicle of rebellion and whip removal

Scattered voting slips marked "Aye" and "No" line the chamber floor, capturing the chaos and control at the heart of parliamentary discipline.

Westminster thrives on a certain kind of theatre and few performances rival the run-up to a backbench rebellion. The whips' office scrambles to contain the rumours, MPs weigh their conscience against their career, and the chamber holds its breath for a vote that can, in an instant, humble a Prime Minister.

For Sir Keir Starmer, this dynamic has become a defining feature of his premiership. His response, a hard line policy of suspension dubbed here as 'The Starmer Sanction', marks a radical break from historical precedent. Where past Prime Ministers managed rebels, Starmer is attempting to purge them. This briefing analyses why that strategy is being tested at a scale and speed unseen in modern political history, and what it reveals about the underlying fragility of a government with a massive majority.

That is what happened in July, when Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and the then Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall had to reach an agreement with (at least some of) the more than 130 rebels who signed Dame Meg Hillier’s reasoned amendment. The move would have stopped the Universal Credit and Personal Independence Payment Bill in its tracks. The climbdown on the proposed changes to Personal Independence Payments (PIP) was so substantial, the Bill was ultimately renamed with the second half of its name removed.

How Starmer has dealt with the fallout from this and other revolts has been unlike most Prime Ministers in recent history. But how does his approach of suspending the whip from more than a dozen MPs compare with the past? Why do these rebellions take place, and what is the real calculus for the rebels? Below, we explore the history, the key players, and the critical effect this new era of dissent is having on the business of government.

Who is currently suspended and who the real rebels are

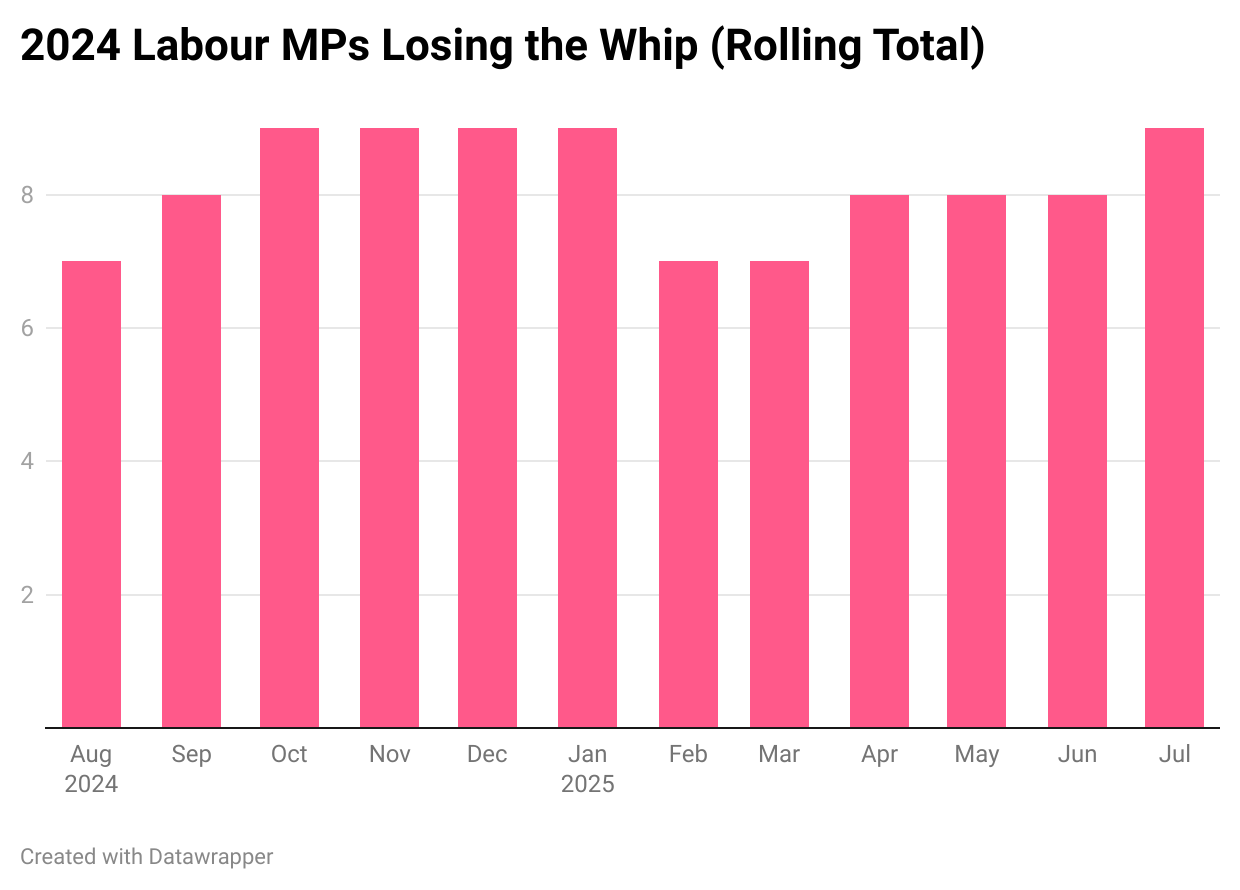

Fourteen months into Labour’s first term back in office, a party that arrived in government promising discipline and control is now managing the fastest emergence of rebellion culture since the Blair and Brexit eras. At least 15 Labour MPs have had the whip suspended since the 2024 General Election, several more than once, and dozens have publicly defied the leadership over welfare reform, Gaza, trade union rights, or internal conduct.

For context: Tony Blair suspended just four MPs across ten years in office. Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has matched that several times over in less than two.

This is not the hangover of Corbynism, or not entirely. The rebels are not confined to the party’s left and the reasons for rebellion are varied: social security votes, trade envoy sackings, WhatsApp messages, and in one case, arrest for sexual offences. Also key is the fact that these votes came with public pressure for the PM. A look at The Public Whip shows several instances of MPs voting against the whip that didn’t receive wider reporting. A key element of any successful rebellion will always be the public pressure it brings to the PM.

What links many of these cases is a pattern of public dissent followed by suspension, with little attempt at reconciliation. The result is that whip suspensions now function less like last-resort disciplinary measures, and more like enforcement tools for public message management.

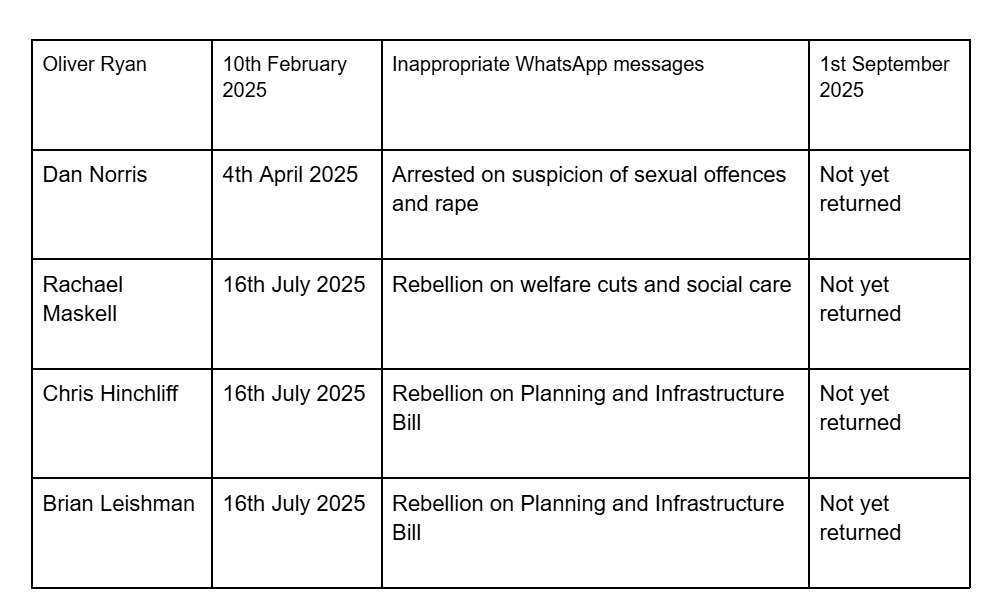

The following table outlines all the Labour MPs who have had or have the Whip suspended.

The July 2024 group

The shift began just three weeks into Starmer’s premiership, when six Labour MPs were suspended for backing an SNP amendment to the King’s Speech calling for the abolition of the two-child benefit cap, a policy Labour had refused to commit to in its manifesto. The MPs were:

Rebecca Long Bailey, Richard Burgon, Ian Byrne, Imran Hussain, John McDonnell and Apsana Begum who were all suspended from 23rd July 2024 to 5th February 2025

Zarah Sultana, who lost the whip the same day, has not had it restored

Despite regaining the whip, many of the returning MPs notably Long Bailey, Burgon and Byrne, have continued to campaign for the cap’s abolition, sign publicly sponsored EDMs, and signal defiance on welfare reform. Begum and McDonnell remained suspended until September 2025, having the whip quietly restored the week before the party conference, where it was reported that the cap would be lifted in some form in the November Budget. Sultana, meanwhile, has moved beyond the Labour tent entirely, and is now co-founding Your Party with Jeremy Corbyn. That, more than any disciplinary action, signals a permanent split.

These MPs share more than just their rebellion date. All were previously aligned with major trade unions (FBU, CWU, Unite), all have public welfare-facing constituency casework, and several have continued to challenge government policy since their return.

If the goal of suspension was to deter further dissent, the effect has been mixed.

The July 2025 purge

A year later, and under mounting pressure over its disability benefit reforms, the government moved again. In July 2025, it suspended another five Labour MPs who had been vocal opponents of the Welfare Reform Bill and broader cuts to social protection:

Neil Duncan-Jordan

Brian Leishman

Chris Hinchliff

Rachael Maskell

John McDonnell

All five had voted against the Bill, and all had a track record of publicly challenging Starmer’s welfare policy direction. Some had also spoken out on issues such as WASPI compensation, winter fuel allowance, or disability casework in the Commons. Leishman in particular had clashed with the leadership over its failure to deliver on commitments to the Grangemouth refinery workforce, a highly visible issue in his Scottish seat.

Their suspensions drew a wave of commentary. One Labour source told The Times the MPs were removed for “persistent knobheadery”, a quote that now lingers awkwardly in most coverage of the incident.

Another loyalist MP told PoliticsHome: “This isn’t about criticism. This is tiresome dickheadery.” McDonnell, for his part, defended his colleagues, saying they had been punished for “speaking up for their constituents and following their conscience”.

The messaging problem

In parallel to policy dissent, the party has also suspended MPs for reasons of internal conduct and reputational damage, but not always consistently.

Diane Abbott was suspended in July 2025 after reiterating past comments about antisemitism and racism. She had previously been suspended in 2023 for almost a year for the same remarks, and this was interpreted as a final breach.

Oliver Ryan was suspended in February 2025 over leaked WhatsApp messages, reportedly sent prior to his election. His whip was restored in September.

Andrew Gwynne MP was also suspended in February 2025, reportedly for involvement in the same WhatsApp thread. His whip remains suspended.

Dan Norris MP was suspended in April 2025 following an arrest for sexual offences and rape. No further public statement has been made by the party.

These cases differ from the amendment rebels in that their infractions were not policy-based but the leadership’s messaging has struggled to explain the thresholds for action. Abbott’s continued exclusion, despite her standing in the party, her honorary title as Mother of the House and past frontbench role, is contrasted with the speed of reinstatement in other cases. Gwynne’s prolonged suspension sits awkwardly alongside Ryan’s reinstatement.

Where Blair often ignored rebellion and let the whips manage dissent internally, Starmer has adopted a high-visibility disciplinary model but without a consistent doctrine to justify who stays and who goes. The result is an emerging perception that suspension is tactical, not principled. It’s not what you do, it's how you publicise it.

The history of backbench rebellions

The backbench rebellion has evolved from a rarity to a core feature of parliamentary tool among MPs. In the post-war period, revolts were whispers, occurring in under 10% of votes, with the 1950s even seeing two sessions of perfect loyalty. The 1970s stirred the pot, but it was under the Blair and Brown administrations that rebellion became a mainstream habit, rising from 21% to 28% of divisions.

The 2010 Parliament exploded this trend into a permanent state of affairs, with 54% of votes seeing rebellions in its first months, a chaos that ultimately consumed Theresa, now Baroness, May’s premiership over Brexit. The lesson for Sir Keir Starmer was clear: today’s backbenchers are willing to wield their votes not as a last resort, but as a tool of influence.

British political parties have long struggled to contain the rebellious nature of their backbench MPs.

As Professor of Modern History at Worcester University Neil Fleming notes, the two-party dominance, that has defined British politics for the last century, has resulted in the Conservative and Labour leaders having to control a broad coalition of ideologies under their respective parties’ banners. For the Conservatives, the defining theme was Europe. What began with 81 rebels demanding a referendum under David Cameron culminated in the ERG-led insurrection that executed Theresa May’s premiership, a rebellion, by percentage, even larger than Blair’s over Iraq. But rebellion is a versatile weapon. Boris Johnson faced his own insurrections over pandemic restrictions, saved only by Labour votes. Rishi Sunak’s Tobacco and Vapes Bill became a stage for leadership positioning, with Kemi Badenoch using a free vote to signal to the party base. The insight is clear: in an age of weak tribal loyalty, rebellion is as much about personal branding and future leadership bids as it is about principle.

Ideologically committed MPs are often the most rebellious once in power. The archetypes are telling: Conservative MP Philip Hollobone rebelled on nearly 20% of votes in government, finding coalition compromise an affront to his principles, while Jeremy Corbyn became a legend of dissent, defying the whip 428 times in a single parliament. Tony Blair’s chief whip famously wrote him off as “simply not worth the effort.”

Critically, neither Hollobone nor Corbyn was ever suspended. This highlights the starkest break with tradition under Starmer. Historically, the whips’ office preferred internal management to public purges. The Labour Party’s eternal civil war over welfare, between those who want to strengthen the safety net and governments that feel compelled to “act tough”, was managed, not eradicated. Blair faced his first major rebellion over single-parent benefits within months of taking office, and serial rebels like Gwyneth Dunwoody wore their dissent as a “badge of honour.”

This history makes Starmer’s predicament familiar, yet his response unique, given his situation. Blair’s massive 179-strong rebellion over Iraq, the largest since the 19th century, saw no suspensions. He could afford such leniency; with a colossal majority, rebels knew they couldn’t actually defeat the government. Starmer now faces the same paradox of a large majority: it lowers the cost of rebellion for MPs, making them more willing to rebel for show, not just for substance.

Instead Starmer’s approach more closely resembles that of Boris Johnson in the early days of his premiership in 2019. In September of that year, Johnson expelled 21 MPs, including two former Chancellors, for defying the whip to block a no deal Brexit. Crucially, Johnson’s actions came when he was running a minority government with his premiership hinging on the success of him delivering Brexit. Starmer, by contrast, has a sizable majority and is much less exposed. History suggests that the question is no longer whether rebellions will happen, but whether a strategy of suspension can realistically contain the inevitable.

Handling the heat

If being seen as the “grown-ups” was Labour’s electoral advantage, the last year has raised a sharper question: what happens when the grown-ups start losing control?

The task of internal discipline, already more complex with a 148-seat majority, has been made harder still by a leadership that demands obedience, but rarely explains itself. And with rebellion becoming a route to influence, not exclusion, the Whips’ Office is increasingly in reactive mode. A three-line whip, the strongest parliamentary instruction a party can issue, is now a regular fixture of Labour business especially on domestic legislation. Technically, defying it can lead to disciplinary action, including suspension or deselection but historically, its enforcement was nuanced. Under Blair, even mass rebellions on Iraq, welfare, or Trident resulted in no suspensions. In Starmer’s government, the three-line whip has become more rigid and its breach more punishable.

This shift is more than procedural. It reflects a broader centralisation of control. Since the resignation of Angela Rayner from the Deputy Leadership, Jonathan Reynolds MP has been appointed Chief Whip, tasked with repairing internal discipline and rebuilding the Labour machine. His brief is part-organisational, part-political. It also follows a growing sense in SW1 that the Starmer operation has lost its grip on its backbenches. But Reynolds is not Gavin Williamson and there is no tarantula on the desk. The disciplinary regime is spreadsheet-heavy, message-focused rather than menace-based. That’s not necessarily a flaw but it is incomplete. There have been comparisons made of the current Whips’ Office to an HR department with a scheduling app.

Meanwhile, Starmer himself has been notably largely absent from division lobbies in the Commons since becoming Prime Minister. He is rarely seen in the division lobbies. MPs, especially those new in July 2024, report they have never had a conversation with the leader at all. This absence undermines traditional whipcraft. Persuasion is interpersonal. Spreadsheets are not.

During the Blair years, discipline was informal as much as formal. Daily meetings between the leader and Chief Whip, Parliamentary Private Secretaries assigned to manage caucuses, backbench rotas for consultation, these were the unglamorous but essential mechanics of control.

Starmer has opted for a different model: pre-vetted candidates, public suspensions, and media management. It works when things are quiet but rebellion is not quiet anymore.

The growing rebellion culture is also fed by success.

The winter fuel U-turn, the softening of Personal Independence Payment reforms, the backtracking on deportation pilots all followed coordinated dissent, sometimes informal, often pre-announced. Labour MPs are learning what the Conservative Party European Research Group (ERG) members once knew: a government with a big majority is vulnerable in surprising ways. There is, of course, no formal rebel group, but there are WhatsApp groups, informal amendment meetings, and media briefings that carry more authority than many select committee chairs. The leadership has not yet worked out how to neutralise this culture without feeding it. And so the problem persists.

This is not yet a full-blown crisis. The legislation still passes. The machinery still functions but the cost of that passage is rising, and the internal logic of obedience is fraying. The Whips’ Office may yet reassert control but it will require more than suspension letters and stern phone calls. It will require a Prime Minister willing to do the politics of leadership: persuasion, presence, and purpose. Far from insulating the leadership, Labour’s majority has become the very thing that makes rebellion manageable.

PoliMonitor Analysis

Sir Keir Starmer is not unique in facing rebellion from his backbench MPs. Far from being a rarity, they have become the norm in Parliamentary life. However, the scale and speed with which he has faced these rebellions, and how he has chosen to deal with them, stand out in recent history. The reasons for the scale of the rebellion over welfare reform are varied.

Starmer’s government has, now infamously, struggled to set a prevailing narrative on where he is taking the country, and the cuts to PIP were seen by many as more tinkering around the edges, rather than the radical reform many in his party thought they would be ushering in, which would have disproportionately hurt a vulnerable group of people. Rather than reflecting a wider strategy, the legislation appeared to some as little more than a budget cut. After facing so much anger on the doorstep over cuts to winter fuel, the message from some MPs was clear: this approach to balancing public finances could not go on.

Beyond the moral case, it is clear that for many, the political risk of rebelling is limited. Much as they wouldn’t want to admit it, the Starmer administration has already shown itself to be willing to change tact based on the input of its backbenchers. Couple that with the fact that the MPs who were initially suspended over the two-child benefit cap have had their whip restored despite continuing to call for its removal, as well as the size of the Government majority, and it appears that there was little to stand in the way of potential rebels joining the cause. Dust on top the stature of Dame Meg Hillier, the Chair of the Treasury and Liaison Committees who tabled the reasoned amendment, and unhappy MPs were given every excuse to rebel.

So when can we expect the next big rebellion on Starmerism?

Reports early in the summer suggested that the Government was already trying to get ahead of concerns over SEND reforms. PoliticsHome recently reported that after delaying the publication of proposals from September to October, there is now a chance that they won’t come until next year. A funding agreement had been arranged already, however the welfare rebellion has appeared to cause plans to be rethought, presumably because the Government is concerned MPs won’t accept the proposals. It is clearly an issue MPs are particularly concerned by, with nine Westminster Hall Debates since the election containing SEND in the title, of which five were moved by Labour MPs.

The conflict in Gaza also has the potential to be another rebellion point.

Labour MPs have been vocal in their opposition to Israel’s actions in the region, and at the conference the Party voted to declare that Israel has committed genocide against Palestinians, which could lead to further pressure on the issue. That said, forcing a vote where MPs can criticise the Government will be difficult. The FCDO rarely tables legislation and as such, the opportunity for MPs to show their disapproval in this way may be difficult.

The truce brokered at the Liverpool conference, facilitated by the last-minute return of several whips, is a tactical peace, not a strategic one. Starmer's successful speech may have placated his critics for now, but the need to do so confirms his authority is more brittle than his majority suggests. The underlying dynamic remains unchanged: his backbenchers have tasted power, and the genie of rebellion will be unlikely returning to the bottle.

PoliMonitor will be here for it all.