Inquiries into Inquiries

Thousands of hand-painted hearts line the National COVID Memorial Wall in London, each representing a life lost during the pandemic, a visual reminder of the grief, accountability, and public reckoning that inquiries like the UK COVID-19 Inquiry seek to confront.

The UK now has more public inquiries running than at any time in its history.

What began as a tool for post-crisis accountability has become a near-permanent feature of British governance. With 24 inquiries either ongoing or announced and a record number initiated since the July 2024 General Election, there are growing concerns from across the political spectrum that the system is no longer delivering trust but consuming it. This is no longer just an issue of transparency or reform; it’s one of political bandwidth and institutional fatigue.

The Rise and Rise of the Inquiry State

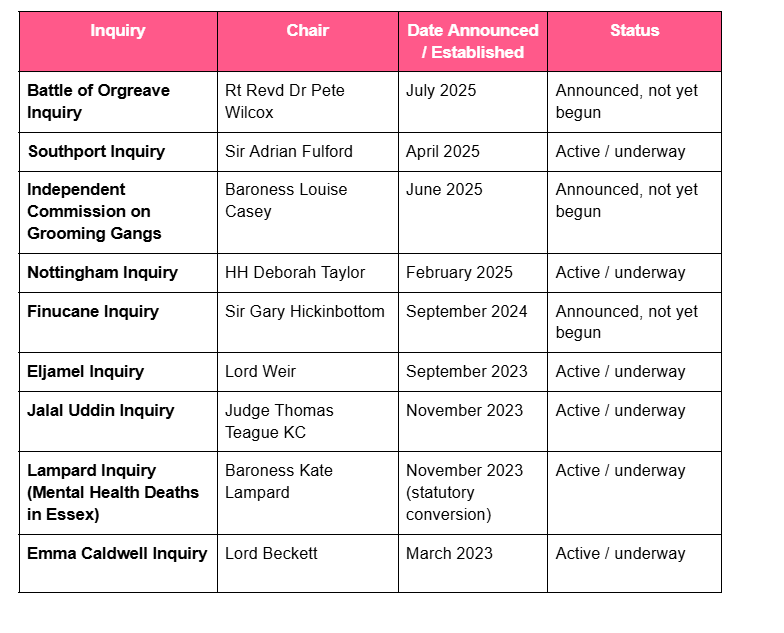

2025 has seen five new inquiries launched in just nine months from Orgreave to Southport, bringing the total to 24, the highest in UK history. These include sprawling investigations into national scandals like Horizon and Covid-19, as well as more recent flashpoints around public protection failures.

What’s notable is not just the number but the political posture they reflect. Under Sir Keir Starmer’s government, inquiries are being used not only to address failures, but to reset relationships with victims' groups, reframe legacy justice issues, and project moral seriousness.

There is a risk, however, that the inquiry has moved from a mechanism of accountability to an aesthetic of it, a tool used to defer blame, delay decisions, and signal reform without enacting it.

Inquiries now function as much in the political realm as the legal one. Ministers retain control over who chairs them, what terms they operate under and when they are launched. This duality of being independent in operation, but political in origin creates a system where power and accountability are constantly negotiated, not automatic. The current list of inquiries spans everything from military misconduct and hospital safety to historical injustices and policing failures. The implication is clear: the government is struggling to stay ahead of institutional failure but the deeper risk is one of governance through retrospection, a permanent backward glance, with few levers to accelerate forward reform.

What Is a Public Inquiry?

A public inquiry is a formal investigation into matters of public concern, established by a UK or devolved government minister. They are independent in operation but politically created, a duality that has shaped both their authority and their vulnerability. Inquiries are typically convened in response to a specific event or pattern of systemic failure. Past inquiries have addressed transport accidents, fires, hospital deaths, pension scandals, military misconduct, and decision-making that led the UK to war.

There are two main types of inquiry:

Statutory inquiries, launched under the Inquiries Act 2005, have legal powers to compel witness testimony and demand the release of documents.

Non-statutory inquiries, by contrast, rely on voluntary cooperation and have no legal enforcement powers but are often faster, less adversarial, and more flexible in structure.

The 2005 Act was designed to simplify the fragmented legal framework that previously governed inquiries. Yet today’s inquiry landscape is arguably more complex than ever both in process and purpose.

What Do Inquiries Aim to Achieve?

While their legal remit can vary, most inquiries attempt to answer three core questions:

What happened?

Why did it happen and who is responsible?

What can be done to stop it happening again?

This structure, popularised by legal counsel Jason Beer KC, frames the model most UK inquiries now follow. Government policy further defines the aim of public inquiries as primarily to “prevent recurrence”, yet critics point out that lessons are not always learned, and recommendations are frequently unimplemented.

Between 1990 and 2024, 54 UK public inquiries made 3,175 recommendations. Many of those remain unadopted. The Thirlwall Inquiry into serial killer Lucy Letby is one of several now conducting its own audit of how many past recommendations have been ignored. The Grenfell Tower Inquiry and Infected Blood Inquiry have both made direct calls for the government to be placed under formal obligation to report on implementation progress.

Who Runs Inquiries?

Public trust in inquiries often rests on the figure at the helm. Since 1990, nearly two-thirds have been chaired by judges. That trend continues in 2025, with all but two of the 24 inquiries led by individuals with legal backgrounds but questions are now being asked about whether legal expertise alone still confers public legitimacy.

The appointment of Rt Rev Dr Pete Wilcox to chair the Orgreave Inquiry, and Baroness Louise Casey to lead the new Grooming Gangs Commission, signals a subtle shift towards non-judicial authority, with an emphasis on moral leadership, public engagement, and institutional experience. This reflects a broader trend: public trust in judges is no longer automatic, and inquiries must now earn it by connecting more visibly with lived experience, professional credibility, and diverse perspectives.

The gender and racial homogeneity of chairs also remains a running critique. Since 2005, just 22% of inquiries have been led by women, with even fewer by people of colour. In an era of heightened awareness around institutional racism and systemic bias, this poses a real reputational risk for the system itself.

The Scope of the System

There are no legal deadlines for inquiries and increasingly, there are no political ones either. Some inquiries, such as Undercover Policing and Hyponatraemia, have taken more than a decade. The average now stands at over three years. That isn’t just a bureaucratic problem, it’s a political one. Inquiries are now routinely announced with no chair appointed, no date confirmed, and no early hearings scheduled. While survivors and campaigners often push for expansive terms of reference, the consequence is that inquiries are launched into neutral space, promised, but not begun.

The process of Maxwellisation, whereby those criticised in a draft report are given time to respond, often further delays publication by months or even years. That may be fair from a legal standpoint, but from a public interest perspective, it slows the delivery of justice and diminishes the impact of findings.

Why Do Inquiries Cost So Much?

Inquiries are expensive and increasingly so. The Bloody Sunday Inquiry remains the most costly ever, with £272.5 million spent at today’s prices. Since 1990, over £1.5 billion has been spent across the UK and devolved administrations on inquiries. The more critical figure is this: 36% of inquiry costs are legal fees. In an era of budget constraint, that has prompted growing calls for oversight mechanisms and budget caps.

The House of Lords Statutory Inquiries Committee has already recommended a strengthened Inquiries Unit, mandatory interim reports, and an online tracker to monitor government implementation. Ministers have yet to legislate for this and without systemic change, the gap between evidence and impact will continue to widen.

The Inquiries Landscape in September 2025

Since entering Downing Street in July 2024, the Starmer government has launched five new public inquiries each politically calibrated to project justice, reform, or institutional resolve. This list tells its own story: Labour is engaging with legacy injustice, state failure, and public protection but it is also relying heavily on inquiries to do the political heavy lifting in response to opposition. Without clear plans to legislate on implementation, the risk is that this becomes a politics of deferral, not delivery.

How Many Inquiries Are Too Many?

Since 1997, there has never been a time when fewer than five public inquiries were running at once. Today’s figure of 24 is not just a record it is, according to former inquiry chairs and Institute for Government analysts, approaching unmanageable. Ministers are under pressure. Under previous Conservative administrations, especially during the David Cameron and Theresa May years, simultaneous investigations generally ranged from 5 to 10. Even during the Blair and Brown eras when high-profile investigations such as the Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) and Shipman Inquiries dominated headlines, the overall total never reached today’s figures.

Many families and campaigners continue to call for additional inquiries including into the 1994 Mull of Kintyre Chinook crash, which the Starmer government has refused. Others accuse the government of using inquiries as a shield from immediate accountability, delaying hard decisions while appearing responsive. At the same time, there is mounting frustration inside Whitehall and Parliament that inquiries are consuming disproportionate time, money, and legal resources without delivering meaningful reform. Recommendations are often ignored or diluted, and criminal trials, where appropriate, must run in parallel, further delaying inquiry outcomes.

The House of Lords Statutory Inquiries Committee, in a 2024 report titled Public Inquiries: Enhancing Public Trust, recommended:

Statutory timeframes and budget caps

An online tracker of government implementation of recommendations

Less reliance on judges, more use of sector experts and diverse panels

Interim reports to provide accountability during long processes

A strengthened Inquiries Unit in the Cabinet Office to enforce standards and share best practice

The government accepted the findings in principle but has yet to legislate.

From Accountability to Exhaustion?

There is a fine line between governing through transparency and governing through avoidance. The UK may now be inching across it. With 24 inquiries either underway or formally announced and more being demanded, from the Mull of Kintyre Chinook crash to social housing failures, the public inquiry system is showing signs of institutional strain, political overuse, and diminishing returns.

Campaigners still see inquiries as vital instruments of truth-telling and redress but inside government, the mood has shifted. What was once a constitutional pressure valve is fast becoming a resource sink, absorbing legal expertise, senior civil service bandwidth, ministerial focus and media oxygen for years, often without resolution. Whitehall insiders speak of “inquiry fatigue”; Treasury officials question the spiralling costs and ministers, who once used inquiries to buy breathing space, are now facing scrutiny over whether they’re merely outsourcing difficult decisions under the guise of democratic accountability.

Certain inquiries have become watershed moments in British public life. The Bloody Sunday Inquiry reexamined the tragic events in Northern Ireland and reshaped public understanding of that dark chapter. The Hillsborough Inquiry exposed critical failures in crowd management and emergency response, leading to lasting changes in public safety protocols. The Chilcot Inquiry’s in-depth review of the UK’s decision-making during the Iraq War challenged official narratives and spurred intense debate over military intervention. Inquiries into Grenfell Tower and the Shipman case uncovered systemic lapses in building safety and healthcare oversight, prompting widespread calls for reform. Each of these landmark investigations not only revealed hard truths but also laid the groundwork for enduring policy change.

Grenfell Tower, covered in white sheeting and bearing a green heart memorial, stands as a stark symbol of national grief and the long wait for justice through one of the UK’s most consequential public inquiries.

The deeper problem is one of credibility drift. When inquiry recommendations go unimplemented, as many routinely do, the legitimacy of the entire process begins to erode. A stark example is the continued presence of the same type of cladding implicated in the Grenfell tragedy still found on homes across the UK, years after the inquiry’s urgent findings. The political risk is clear: inquiries risk becoming less about learning lessons and more about staging consequences, solemn rituals of accountability that deliver no meaningful change. In this model, inquiries serve as substitutes for action, rather than the prelude to it.

The Starmer government has so far used inquiries as a signal of moral clarity and state seriousness particularly on legacy justice, public protection, and institutional failure but symbolism has a shelf life. The next test is whether Downing Street can transition from convening inquiries to delivering on their outcomes. If not, the UK's most powerful instrument of institutional introspection may soon become its most potent source of disillusion.